Road Construction in the USA – The Racism of Highways and Freeways

Steppenwolf's highway anthem "Born to Be Wild" painted a picture of the American highway and freeway system that still shapes our imagination today: Freedom, vastness, a view that can reach a hundred miles, an endless ribbon of asphalt stretching across America. But – this is not the whole reality..

On many car trips in my old VW bus from Oakland, where I live, to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan – 3.500 kilometers – I was always caught up in this feeling: The horizon opens up. Setting the cruise control to 70 miles per hour, out into the open, letting your mind run wild.

There are stretches of road where you drive and drive, no other car far and wide, no one overtakes you, no one comes to meet you. On the FM band on the radio just static, over the medium wave there are still a few stations: Farm Talk, Gun Talk, Oldies and a station with Mariachi music. A sense of freedom, the dream of America.

Over mountains, through deserts and forests

On the long highways you get to know America. Mile after mile, the road just won't end, over mountains, through deserts and vast tracts of forest, and I wonder how the settlers once made their way here on their horse-drawn wagons without roads, trails, cross-country, not knowing what was to come. Even today it is arduous.

When I get on Interstate 80 in Oakland, I stay on 80 all the way to eastern Nevada. Highway 93 crosses the freeway, a few gas stations, a few fast food restaurants. Heading north, to Idaho, ahead of Twin Falls further east. Blackfoot, Idaho Falls, Big Sky, Yellowstone National Park. At Bozeman on Interstate 90, 800 miles straight through Montana, North Dakota to Minnesota.

It's a long lonely highway when you're travelin' all alone

And it's a mean old world when you got no-one to call your own

And you pass through towns too small to even have a name, oh yes

But you gotta keep on goin', on that road to nowhere

Gotta keep on goin', though there's no-one to care

Just keep movin' down the line

"(It's A) Long Lonely Highway" by Elvis Presley

From Oakland to Michigan it takes me about 40 hours for the 3.500 kilometers long. Fill up with gas, walk the dog a few steps, power naps, sleep for 30 to 45 minutes, then move on. The road system is well developed, traffic minimal. Metropolitan areas I bypass.

Even if you have a speed limit on all highways and most freeways, you can still make good progress. The road system excellently connects almost all corners in this vast country. It is a system with a plan.

Expansion of the road network after 1956

In 1956, the so-called National Interstate Defense and Highways Act was passed: the largest road-building project in American history up to that time. With an unbelievable $25 billion at the time, more than 66.000 kilometers of freeways and highways, expressways and rural roads, be built crisscrossing the United States. A network of roads that should connect America's metropolitan areas.

The word defense was intentionally used in this bill because, for one thing, funds from the defense budget were used for the freeway project. Second, nearly all continental U.S. air bases were connected to this network for rapid response in the event of a ballistic or nuclear attack by the Soviet Union.

Military reasons for road expansion

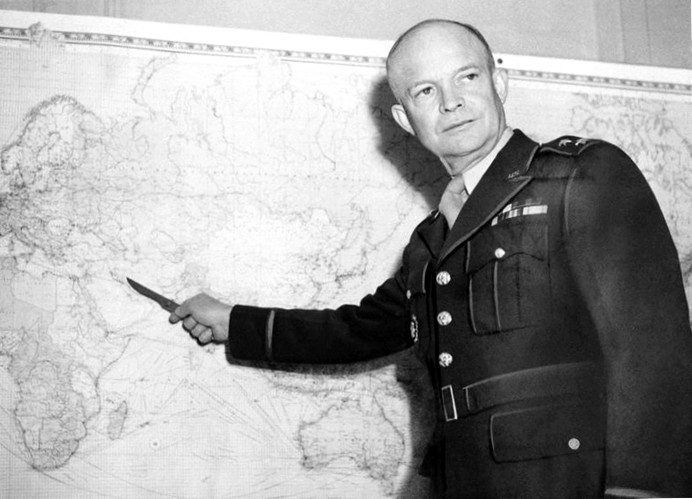

In a memo to Congress on 22. February 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower the need for widespread construction of a freeway and highway network in the U.S. also with military reasons.

In the event of a nuclear attack on our major cities, the road network must allow for rapid evacuation of the target areas, mobilization of defense units, and maintenance of any major economic facilities. But the current system in critical areas would be an incubator for clogging within hours of an attack.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Eisenhower's enthusiasm for a U.S.-wide and unifying freeway system stems from his personal experience. Eisenhower participated in the U.S. Army's first "Transcontinental Motor Convoy" from Washington DC to San Francisco in 1919 as a 28-year-old lieutenant colonel. Departure was on 7. July, arrival at 6. September. 62 days "on the road" for a distance that today can be covered in 42 hours.

Eisenhower's experiences during the war in Germany (here at London headquarters) also led him to expand the road network in the U.S. © picture alliance / AP

It was coast to coast over the Lincoln Highway at the time, the first highway designed for automobiles. An arduous journey on a bumpy dirt road through 13 states, requiring bridges to be stabilized for the convoy along the way, vehicles to be pulled out of the mud and, because of the poor road surface, repaired several times.

Then there were also his experiences in the former enemy country of Germany. "The old convoy made me think about the good two-lane highways, but in Germany I saw the wisdom of a wide ribbon across the country," he writes in his 1967 book "At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends" in the chapter "Through Darkest America With Truck and Tank".

The USA as a car nation

The United States had undergone a sea change after the end of World War II. America has become an auto nation, which is also characterized by the so-called G.I. Bill was promoted. In 1944, the U.S. Congress had passed a law to help World War II veterans financially upon their return – by providing unemployment benefits, cheap loans for buying a house and starting a business, plus paying for tuition fees.

However, this law did not benefit all war returnees in the same way. Because it was still modeled on Jim Crow laws, those racial laws in many American states that sealed a strict separation between whites and African-Americans after the American Civil War. The result has been that g.I. Bill helped mostly white war returnees, but African-Americans mostly went away empty-handed.

As a result, blacks in the U.S. became further economically disconnected, while many whites moved their families to the suburbs in a newly built home to turn their backs on the crowded big cities, as Ben Crowther of the nonprofit organization The Congress for the New Urbanism, a group of urban planners, explains. Urban planning had grown significantly in the 1950s. "The ideas that promoted this stood for a new lifestyle, to promote suburban living. This idea that there was a possible separation between where you worked and where you lived."

The USA, a country of drivers: Convertible traffic jam at Daytona Beach in Florida around 1959. © picture alliance / United Archives / Erich Andres

At the same time, this idea was also linked to the fact that suburban life was primarily a white lifestyle: white suburban life at the expense of other communities, especially communities of color, which stood in their way. "That's how methods like red lining came about, even though it had been around since the 1930s. But it also gave us our highway and interstate system in the cities…"

Disadvantaging African-American neighborhoods

Red Lining: the term stands for an imaginary barbed-wire draw in U.S. cities and towns that became an invisible but palpable reality for decades, especially for African-Americans. The government in Washington, through what is known as the National Housing Act of 1934, had divided neighborhoods into distinct areas.

The letter A stood for an all-white neighborhood, desirable for the middle class. Just one colored family in the area pushed the grade from A to B, and that had dramatic consequences, because the neighborhoods below A were specifically disadvantaged. So African-Americans were pushed into neighborhoods where it was harder to get mortgages or insurance, where there were fewer business and urban development investments made.

These neighborhoods fell behind compared to white neighborhoods and suburbs. Until the 1970s, this form of urban discrimination remained common practice, with consequences to this day.

Highway construction with consequences

"If we look at the construction of highways, there were courses of roads chosen primarily for racist reasons, by racist highway builders," says Ben Crowther. "A system was established that a road planner would pick the road where there was the least opposition to fear, both financially and politically." Among a road builder's biggest costs would be in acquiring land through eminent domain compensation payments. "That's why it just hit those neighborhoods where the homes of people of color had been devalued anyway because of the red lining. So when you look around for the cheapest land, it's right here, right in these neighborhoods." The least financial resistance for highway builders.

"Politically, too, there were no influential forces here in the 1950s and 1960s to advocate for these neighborhoods when their homes were simply in the way of a proposed highway. All of this led to the highway network we have today, which did a lot of damage when it was built and still impacts the same neighborhoods, as well as the descendants of those who were there back then."

Freeways for white suburbanites

This freeway story begins with World War II. "The freeways were built to be able to move tanks quickly from one city to another, and then also, as you can see in West Oakland, because a lot of people who had money and were white and were allowed to live elsewhere moved away, to the suburbs, like Hayward, San Leandro, Pleasanton or Walnut Creek. They needed a quick connection to the city, to Oakland and San Francisco," says Quinton Sankofa. He's a "community organizer," activist for a more equitable life in Oakland, California. The former "Black Town," as Oakland was long called because of its large African-American population, was especially hard hit.

So the freeways were built to connect the suburbs to the inner cities, which were pretty much black all over the country, Sankofa points out. "You really find that everywhere in the U.S. The poor blacks stayed in West Oakland. The whites with money moved away to the outside. These were the reasons."

So the freeways were planned "to be drawn right through West Oakland," right through 7th Street, Oakland's black cultural district. "This is where that wonderful jazz, art and culture that people associate with Oakland today came from. This was all in the 1950s, when America dreamed this suburban dream and fueled it with huge amounts of money. But no money was invested in the inner cities."

Destroyed, disconnected neighborhoods

West Oakland starts just behind the Bay Bridge that connects San Francisco and Oakland, right next to the harbor and sewage treatment plant. Eastbound 580 to the Central Valley and southbound 880 to San Jose split here and are routed around West Oakland. Then there's the 980, which is just two miles long and connects the 580 and 880 freeways parallel to downtown.

This very 980 separates the historically African-American neighborhood in West Oakland from the city center. A freeway that seems gigantic and has long been considered completely unnecessary. "A five-lane freeway that was once originally intended as a feeder to another Trans Bay bridge, but that was never built," as described by city planner Chris Sensening.

The original plans for this downtown freeway seem gigantic and like the pipe dreams of unleashed city planners. The 980 was to be a feeder to a brand new and never built bridge connecting Oakland to the southern part of San Francisco and relieving the Bay Bridge built in 1936. A bridge that would have further fractured and burdened Oakland.

Cruisin' down the highway

In my fine machine

Lake pipes really singing

The engine sounds real mean

Sound is a gas

Sound is a gas

Well, I can hardly wait

To hear that big V8

Ooh, I can hardly wait

Yeah, yeah, yeah

"Cruisin' Down The Highway" by The James Gang

Just four blocks from the 980 Freeway stands Oakland's massive City Hall. Here on the second floor, Mayor Libby Schaaf has her office. She was born, raised in Oakland, is a close confidant of Vice President Kamala Harris.

Schaaf made his career here in Oakland. But it wasn't until she moved into City Hall in 2014 that she was made aware of the 980's daunting neighborhood problem. "When you look at the 980, it's depressing," she says. It runs recessed, she says, reminding her of a moat. "As someone who knows the ugly history of these and many other cities in America, it always looked to me like a racial moat that protected downtown from the black neighborhood of West Oakland. Interestingly, yes, it was built as a feeder to another bridge that never existed. So there is very little traffic on this freeway. It's not needed. There is an unnecessary scar on the face of my beloved city."

From the highway to the shopping center

City planner Chris Sensening knows all too well the history of 980, a freeway that was planned back in the early 1960s and, after many delays and court rulings, was finally completed in 1985, at a time when it was already clear it was no longer needed. The actual plans for this urban freeway, however, were quite different. A brand new and covered shopping mall should be built in Downtown. "The shopping center had promised a lot of jobs. Politicians, as well as quite a few neighborhood groups that were originally opposed, eventually voted in favor of building the freeway."

Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf (l) with San Francisco Mayor London Breed (r): Schaaf advocates for dismantling racist infrastructure. © picture alliance / abaca / Pool

So it was "a story of power and hope," Sensening said, "that in the end led to the freeway being built and West Oakland being split off from Downtown." The mall was never built. "The idea for this mall was something that wouldn't have done much for the city anyway. It was like a piece of gold that was held up to people but wasn't actually meant for the people of Oakland. Ramps to and from the freeway should lead directly to an underground parking garage. This is one of those examples of separating the wealthier, white suburbs from the inner cities."

Discussions about city planning mistakes

From the lowered freeway straight to the shopping temple, no one should have even had to see the streets of African-Americans in West Oakland. The 980 was supposed to be the feeder freeway for all those who lived east of Oakland in the suburbs of Orinda, Moraga, Walnut Creek and Danville. But neither the huge shopping mall nor the second bridge were realized.

The freeway, on the other hand, was built. Houses were torn down or moved, in the end leaving this massive structural scar in the heart of the city, as described by Mayor Libby Schaaf. "I grew up in Oakland at a time when it was still seen as a black city. When I was young, there was this White Flight, the white extract."There wasn't the awareness of segregated and white neighborhoods back then, he said. "But it becomes quite clear when you look more at the history of racial conditions on real estate that have existed for many homes in Oakland as well, showing how government itself has been part of racism, segregation and discrimination. I never thought in the nearly eight years I've been mayor that I'd get to the point where we're talking broadly about deconstructing a racist freeway that was only there to separate and divide."

Libby Schaaf points to a broad discussion that has only recently begun. Not only in Oakland, but in many cities in the USA: in New York, Minneapolis, Detroit, Miami or even in New Orleans.

After decades, the impact of these downtown freeways is now being reported more frequently. About how city planners in the 1950s and 1960s drew freeways from inner cities to the suburbs without regard for existing and evolved neighborhoods, especially African-American ones. This debate has picked up steam in recent years.

Black Lives Matter strengthens the discussion

"It's fair to say that the catalyst for it was George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement," says Nate Miley, who has been supervisor for Alameda County, with Oakland as its largest city, since 2001. He's been putting his finger in the historical wounds for a long time now. "I do think that was the trigger that set everything in motion. But by then, there was also a foundation that had built up over time." The civil rights movement and other events that pointed out discrimination and historical mistakes. "Martin Luther King once put it this way: 'The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice'. I believe that too, that's what's happening. He further flexes. George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement are just another push to recognize historical wrongs and see if they can be addressed."

But the historic mistakes in urban planning cemented by the construction of multi-lane freeways through African-American neighborhoods have also become topics of political contention in the U.S. Fox News, for instance, the conservative, Trump-affiliated news channel, doesn't see racism in these city planning structures.

The 980 freeway is not the only problem in West Oakland. The district is framed by freeways: 880s, 580s, plus the Bart, the regional subway that runs noisily above ground through the neighborhood here. There's also the Port of Oakland, one of the largest on the U.S. West Coast. Around the clock, container ships are handled here, trucks with overseas containers thunder across the roads, long freight trains pass by. Then the big mail distribution center has also been located here in the face of opposition from the public, and that too is bringing more trucks to West Oakland.

Respiratory illnesses because of the exhaust fumes

The neighborhood is considered particularly affected when it comes to air pollution in Oakland due to the freeways and diesel exhaust from ships and trucks. The result: more asthma and respiratory illnesses. Calls for help from the neighborhood have been repeatedly ignored. Every time there was a major construction project, the Black community was promised that it would bring jobs to the neighborhood, but every time, it was mostly others who earned it.

Exhaust fumes from container ships at the Port of Oakland primarily affect the African-American community. © picture alliance / photo agency-online / Blend Images / Tom Paiva Photography

Supervisor Nate Miley sees the fight against 980 as a sideshow, not a big priority for him as a local politician. "It would certainly be more symbolic, because just deconstructing the freeway wouldn't go to the roots of racism and injustice," he says – and yet it's also clear to him that this is about much more than just deconstructing a freeway. "Although I haven't made up my mind whether I'm for or against it, it's also clear to me that this symbolic act would also show that we as a society are capable of righting historical wrongs that have been done to People of Color." So it would be a step in the right direction.

Racism hurts everyone

Mayor Libby Schaaf has tried to right some wrongs in her nearly eight years in office, including giving land back to the Ohlone people, Native Americans who lived here in this area before whites settled here. For Schaaf, it's clear that coming to terms with deep-rooted racism in the U.S. also begins with such rather "symbolic gestures," as Supervisor Nate Miley called it. "I think systemic and structural racism is the biggest challenge of our time," she says. "We as a country have systematically, through legislation and through public investment, disenfranchised and robbed a large community: of talent, of health, of wealth, of contributions from large segments of the people-of-color community." All would be better off "if we lifted up people who had been systematically excluded from development," Schaaf points out. He said that's just true of this infrastructure, which has a divisive and separative effect, and the issue of environmental justice.

"There's another debate here in Oakland about a freeway that trucks aren't allowed to drive on," she says. This freeway runs along a more white and affluent part of the city and has stricter regulations than the freeways along the poorer, mostly black and brown neighborhoods, through which all the diesel trucks are routed that are banned on the other one. "People are now wondering why that is, why is it that there are these additional exhaust fumes only where there is the most air pollution anyway."Covid has shown that these health disparities are exacerbated when it comes to something like a pandemic. They are not the result of a personal decision, he said. "They have come about because we as a government have not only enabled them, but often created them."

Deconstruction planned

Oakland mayor expresses optimism that 980 will be deconstructed. She sees it as a positive sign that the California Department of Transportation CalTrans is currently preparing a comprehensive report on the pros and cons of deconstruction. In particular, attention should be paid to how traffic will flow in Oakland in the future if the 980 is no more.

The funding needed for this in the Biden administration's infrastructure plan is also a good sign that America is learning from its history, Libby Schaaf said. Billions of dollars just to deconstruct historic mistake as Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg announced at White House. "I'm still surprised by the fact that some people express surprise when I point out that a highway that was built just to separate white and black neighborhoods, or when there's an underpass in New York that was deliberately built so low that no bus carrying children from primarily black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods can get to the beach, that that was obviously racism that went into the planning," he says. "I don't think we have anything to lose by being aware of this. But we have everything to gain by understanding this and changing it. That's why the Connecting Neighborhoods program exists, billions of dollars that we want to put to work immediately."

Whether all this succeeds is questionable. Because all of these plans, the provision to dismantle freeways, of historic misplanning, depend on majorities in Congress and who sits in the White House. Of how you look at American history, at this country itself. Is the U.S. "God's own country," the best nation in the world where mistakes have been made but where mistakes are not being addressed? Or is the U.S. a society where mistakes are made and also admitted to? In the deeply divided United States, the answer is still open.

Racism instead of unlimited possibilities

Long highways and freeways. The further west you go, the straighter they stretch across the country. Straight ahead, coast to coast. On these endless highways, the U.S. seems limitless. It is always a new experience to drive through the United States of America. These never-ending highways have become a symbol of America's freedom through stories and movies.

The many stickers, the many "stars and stripes" on motorcycles, pickups, cars and trucks symbolize a country where many are proud of what has been accomplished here. Eisenhower's visionary National Interstate Defense and Highways Act of 1956 is certainly among them. It connected American cities and towns, deepening cohesion in this diverse country with its diverse interests. But what some saw as freedom became for others another chapter in the long history of racism and discrimination in the "land of opportunity".