The curse of hate and superstition

LWF-supported women's cooperative fights gender-based violence in Nepal

LALITPUR, Nepal /GENF (LWI) – Today, when neighbors call her names, Rita Lama presses the record button on her cell phone. "Such recordings are evidence if I have to fight a case in court," she says. Lama has suffered numerous types of gender-based violence in her home village of Devichour, Nepal. Through a local cooperative, the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) showed her how to protect herself.

According to official statistics, half of all women in Nepal will face violence at some point in their lives, and one in four women has suffered violence in the past 12 months. Mental violence is the most commonly reported (40 percent), followed by physical violence (27 percent) and sexual violence (15 percent).

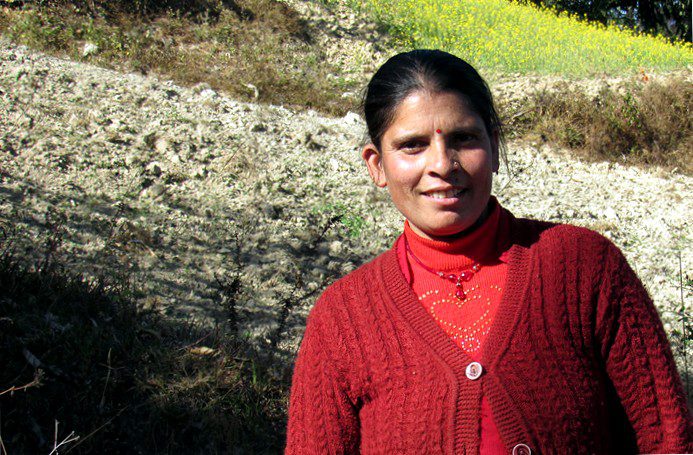

Rita Lama (you can see her community of Devichour in the background) – a strong woman who faced discrimination, superstition and violence.

Early marriage and witch hunt

Lama was still a teenager when she got married. Her husband was a good friend. Marriage for her was, among other things, an escape from life with her father, who was an alcoholic. "I was only 16 years old when I ran away from home to marry him," recalls Lama. Marital bliss lasted only until she gave birth to two little girls. Her husband was indifferent to her and the children, tortured her psychologically and beat her.

She left her husband, but the violence did not stop. Eventually Lama went to the police. At the police station, her husband apologized and soon went abroad to look for work. He has been away for years now, sending money to his family – this is not uncommon in Nepal. After he left, the neighbors began to accuse Lama of witchcraft.

Witch hunts are a common form of gender-based violence in Nepal. In a society that is highly spiritual, some people believe that misfortune is caused by spirits and magic spells. Accordingly, they look for culprits for evoking such ghosts. Defenseless women often become targets in this regard: Widows or women whose husbands are gone, older women or those who are very poor, belong to a lower caste or challenge traditional patriarchal society.

The village of Devichour, a five-hour drive from Kathmandu. The people there live from agriculture, animal husbandry and small handicrafts.

Being accused of witchcraft can be momentous. Lama does not want to talk in detail about the abuse she was subjected to. "When I would walk past their houses, people would bring their children in and tell them I was a witch," she says, crying at the thought of it.

Human rights observers report that women who are considered witches are often severely physically abused or even killed. Often the perpetrators come from the family circle. In many cases, victims do not dare to go to the police. "I thought about killing myself, but I didn't do it out of love for my children," says Lama.

Support from the "didis

Lama's situation caught the eye of Subhadra Bajagain, chairwoman of the Shree Devi women's cooperative in Devichour. With the support of SOLVE Nepal, a local partner of LWF Nepal, the cooperative helps women in difficult situations and is committed to combating gender-based violence.

Subhadra Bajagain, chairperson of the Shree Devi Women's Cooperative in Devichour and a human rights activist, has supported Rita Lama in her fight against discrimination and abuse.

The women from the cooperative were the first in a long time to talk normally with Lama. They made the neighbors aware that their behavior could have legal consequences and informed Lama of her rights.

In 2014, the Ministry of Women, Children and Welfare of Nepal had enacted a "Witchcraft Law" to – as it says on the Ministry's website – "empower women, especially those who suffer from poverty (…) and are socially weak or otherwise disadvantaged." Offenders can now face fines of up to 1.050 USD and received prison sentences of up to 10 years.

Knowing this legal framework finally gave Lama the means to fight back. "In 2015, neighbors called my daughters vicious names and accused them of learning witchcraft," she says. "I was indignant and contacted the nearby police station." An audio recording of the incident served as evidence of the crime. The neighbors then received an official warning and had to sign that they would not use such violence in the future.

Since then, the people of the village have left Lama alone. "They still talk behind my back, but I don't care. The didis (sisters) from the women's cooperative support me," she says.

A new life

Considering the defenselessness of Lama and her family, the cooperative granted her a loan of 30.000 Nepalese rupees granted (300 USD), which Lama has invested in agriculture. "She pays back the loan on time," says Chairwoman Subhadra.

With LWF support, the cooperative has been able to create livelihoods and mediate conflicts in Devichour as well as in seven neighboring villages. "The LWF has provided the money to start the cooperative, it has promoted it through different types of trainings, and it has linked it to banks and to the Nepal Federation of Saving and Credit Cooperatives )," says Nabin Dahal, project manager for LWF Nepal.

Rita Lama says women must be prepared to defend themselves. "Even family members can be perpetrators. I now realize that I am not alone in the fight against discrimination. Organizations like the LWF Nepal and the Nepalese police are there to protect me."

Photos and article by Umesh Pokharel of LWF Nepal. Editing and translation: LWF Communications Office.

The LWF is proud to be part of a religious alliance that aims to end violence against girls and young women. We believe that activism to promote equal and respectful relationships is good news all year round, wherever we are and whoever we are.